Misdemeanour, Felony and Bankruptcy

When thee builds a prison, thee had better build with the thought ever in thy mind that thee and thy children may occupy the cells.

Elizabeth Fry 1780-1845

Prison Reformer

Tracing your family history can be a dicey business. We are all descended from a huge variety of types of people. As the family tree reveals its hidden branches, our research will uncover ancestors of different status and level of education, rich and poor, successful men and bankrupts, hard workers and shirkers, sane and mad people, honest folk and dishonest. The more that we delve, the more stories we will find and some will be less palatable than others.

Naturally we love to report the success stories…the ancestors who rose from obscurity to become leaders in their field, those who made their fortunes on the back of hard work and entrepreneurism…but we owe it to our relatives and descendants to also report honestly the events of which we may not be so proud. This article is about crime and punishment. I must admit to being a bit disappointed that my father’s line contains men who skirted the edges of the law…no highwaymen, bank robbers or murderers, thank goodness, but nevertheless men who occasionally got into trouble and were sometimes tried in court. Some were acquitted, one found guilty and punished, one sent to the debtor’s prison.

The facts that we uncover may not explain the whys and wherefores of the individual crimes of centuries past. However, historians have given us some clues. For many families of the industrial revolution and beyond, life could be successful but loss of income, ill health and other adverse circumstances often drove people to unlawful acts and there was a worrying increase in crime in the early 19th century. Most petty crimes would have been associated with socio-economic conditions and many, such as violence and theft, were committed by young males. Young females’ crimes may have been associated with destitution, prostitution, abuse and despair. Being poor meant that you were more likely to be living near criminals, be the victims of their crimes and be sucked into criminal ways yourself.

It’s a big, big subject, so we’re going to take only a brief look at crime and punishment from the 17th to 19th centuries and then at the Wakefield House of Correction, York Castle Prison and Rothwell Gaol, where records indicate that my culpable ancestors were taken. Lastly, we will look at the case histories of those family members who skirted the edge of the law.

Punishments in the 17th Century

Felonies (serious crimes), as defined by common law, were originally punishable by death; misdemeanours (lesser crimes) by a range of non-capital punishments. Punishment was harsh for those convicted. In 1688, the number of crimes carrying the death penalty was 50. Ways of escaping the death penalty were: Claiming Benefit of Clergy or Claiming Sanctuary in a church.

Benefit of Clergy

Benefit of clergy was an historic benefit. The clergy and others associated with the church might escape the most harsh punishments for some crimes and given a lesser punishment by using a mechanism that dated back to the middle ages, called “benefit of clergy”. This right allowed the church to punish its own members and the court would hand over the prisoner to church officials for the sentence to be prescribed.

Since it was difficult to prove who was affiliated with the church, convicts who claimed benefit of clergy were required to read a passage from the Bible. Judges usually chose verses from the 51st Psalm, which was termed the “neck verse”, since it saved many people from hanging.

oldbaileyonline.org

Because too many convicts had been getting off too lightly by benefit of clergy, murder, rape, highway robbery, burglary, horse-stealing, pick pocketing and theft from churches had now been proclaimed to be “non-clergyable”.

Branding

Convicts who successfully pleaded benefit of clergy, and those found guilty of manslaughter instead of murder, were branded on the thumb (with a “T” for theft, “F” for felon, or “M” for manslaughter). The branding took place in the courtroom in front of spectators.

Sanctuary

Another way of escaping the death penalty was to claim Sanctuary in a Church. There were three sanctuaries in Yorkshire, at Beverley, Ripon and York. A person claimed sanctuary by putting their hand on the door knocker or reaching a prescribed part of the church, especially a “frith stool”. The word “frith” is of Anglo-Saxon origin, and denotes “peace, security and freedom from molestation”. It was usually situated near the high altar and was considered to be the safest place for refugees to reach. Sanctuary was for only 40 days after which the refugee must give himself to the authorities or perhaps escape and seek passage out of the country. Some of the large cathedrals housed facilities for refugees to stay indefinitely. The practice was outlawed in 1624.

Hanging

Hanging had been used as a form of capital punishment as early as the 5th century and had been introduced by the invading Anglo-Saxons. William 1st (the Conqueror) had replaced hanging by castration and blinding, but it came back into use with King Henry 1st (William’s fourth son). Hanging was to become the principle punishment for crimes attracting the death penalty and could be ordered by Assize Court judges. Children as young as 8 years old could be hanged in additional to adult females and males. At this time all hangings took place in public. The idea was that watching the hanging would deter the onlookers from committing crime. In reality it just became public spectacle, which could become either festive or riotous.

Early hangings were by “short drop”, when the victim was suspended by a rope until death by strangulation occurred, which could take several minutes. In the 19th century, this was replaced by long drop hangings and different methods were tried to ensure that death was quick and less distressing. Hanging was in use in the UK until 1964.

Beheading

Beheading with a sword or axe goes back a very long way in history because, like hanging, it was a simple and practical method of execution in early times, when a sword or an axe was always readily available. When an axe was use, the prisoner placed his head across a block and the executioner brought the axe down through an arc and struck the neck full on…more than one stroke might be necessary. Where a person was to be decapitated with a sword, considered an act of mercy, an executioner’s block was not used and the prisoner was generally made to kneel. A skillful swordsman could sever the neck with a single stroke.

Gibbets and Gibbeting

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, gallows or executioner’s block). The West Yorkshire town of Halifax is noted to have had a gibbet in the form of an early guillotine or beheading device, which was in use there until the 17th Century. It is not known when the Halifax Gibbet was first introduced but the first recorded execution in Halifax dates from 1280. The Halifax guillotine was a tall, upright wooden frame, 15 feet high. The blade was an axe head attached to a wide wooden block, which slid in grooves in the uprights to control the blade’s direction of travel. This device was mounted on a large square platform 1.25 metres (four feet) high. When the prisoner placed his head on the block on the platform, the blade was allowed to fall and sever the head in a single blow. (The guillotine was still the official method of execution in France until the abolition of the death penalty there in 1981). List of persons executed at the Halifax Gibbet 1541-1650

However, “Gibbeting” refers to hanging the criminal’s dead or dying body on public display from a gallows-like structure, or within a gibbet cage, also called “hanging in chains”. Judges occasionally ordered that the bodies of murderers who were to be executed should be afterwards “hung in chains” near the scene of their offence “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder”. Gibbeting could also be used as the method of execution, with the prisoner left to die of exposure, thirst and/or starvation.

Hanging, Drawing and Quartering

Men found guilty of high treason would be sentenced to be hanged, drawn (cut down while still alive), and then disembowelled, castrated, beheaded and the body quartered (dismembered). Although there were not a huge number of such executions carried out, the greatest number carried out by this method were used in the 17th century in the Farnley Wood Plot in West Yorkshire in 1663, when 26-six men were arrested, imprisoned and found guilty of treason. Most were hanged, drawn and quartered at York. The practice was eventually abolished in England in 1870, though the last such punishment had been carried out in 1788.

Burning at the Stake

Men and women found guilty of witchcraft or treason were often sentence to be burned at the stake. It was a terrible death and executioners often strangled women before setting the stake alight, to relieve their suffering.

Whipping, Pillory and Stocks

Some less serious crimes, such as drunkenness, swearing, lying or insubordination, resulted in the convicted person being shamed and humiliated by being publicly whipped or placed in stocks or pillories.

Stocks were heavy wooden boards placed at ground level, which restrained the ankles and sometimes also wrists in holes between two boards. The pillory required the prisoner to stand up whilst his head and wrists were restrained and was considered an even harder punishment. Stocks and pillories were set up in the street or in a public place such as in front of the church.

The criminal, once restrained, was then pelted with rotten eggs and vegetables, excrement or the by-products of the slaughterhouse, or subjected to other degrading treatments by members of the public. The main point was to publicly shame the offender and the punishment only lasted a few hours. However, it was no easy punishment and occasionally a prisoner would actually die from mistreatment, so it was something to avoid and the threat acted as a deterrent. In one case, four Englishmen who had unfairly accused somebody of a crime were pilloried and pelted with stones, by an angry crowd, until they died.

Imprisonment

At first, prisons were used as holding placed for people awaiting trial and punishment, rather than as a punishment in itself. By the 17th century, imprisonment was used as a sentence in addition to some other sentence such as being whipped or with hard labour. Convicts might be whipped within the prison walls or publicly before a crowd.

First Use of Penal Transportation

From the early 17th Century, England began to transport convicts and political prisoners, as well as prisoners of war from Scotland and Ireland, to its overseas colonies in the Americas. This was carried out at the expense of the convicts or the ship owners. Prisoners returning before their seven year sentence was expired were subject to the death penalty.

18th Century Capital Crimes

Investigation and conviction were a bit hit and miss until the mid 1700s with the beginnings of professional police forces, notably the “Bow Street Runners” and the Metropolitan Police. The majority of cases were heard by magistrates rather than juries, but the most serious crimes were referred to the Crown Courts which sat at quarterly assizes in large towns and cities.

In spite of horrific punishments still being in place, rising crime was the cause for much concern in the 18th century. Theft rates in particular became alarmingly high. In the hope of deterring such crimes, more and more became subject to the death penalty. The Waltham Black Act in 1723 established a system, to become known as the Bloody Code, which imposed the death penalty for over 200 offences. Below are a few, some of which are very surprising:

- Impersonating a Chelsea Pensioner

- House-breaking

- Forgery

- Destroying turnpike roads

- Cutting down trees

- Unmarried mother concealing a stillborn child

- Arson in a Naval Dockyard

- Being in the company of gypsies for a month

- Malicious maiming of cattle

- Damaging Westminster Bridge

- Poaching

- Wrecking (Stealing from a shipwreck)

- Begging without a license

- Stealing from a rabbit warren

- Pick pocketing goods worth more than a shilling

- Stealing food

- Being out at night with a blackened face

Executions, sometimes several at once, were performed in front of large jeering crowds.

Imprisonment with Hard Labour and Transportation

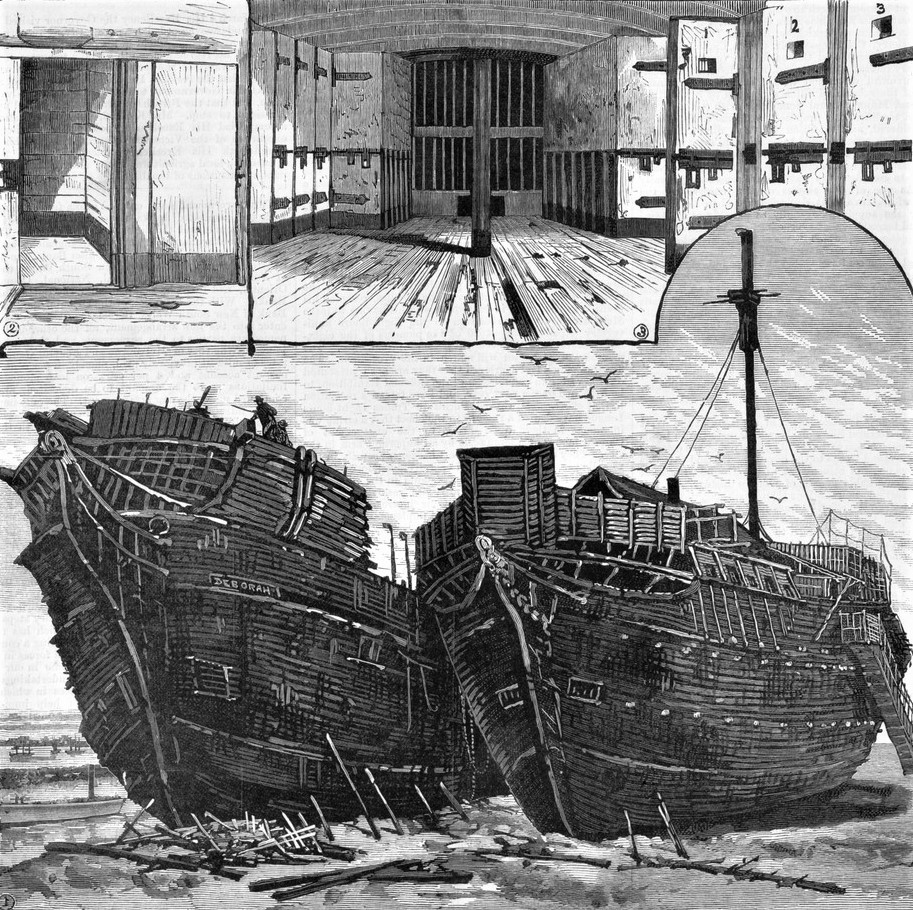

For misdemeanours, branding and whipping were still enforced. Now, for other non-capital crimes, imprisonment on the “hulks” and transportation to the Americas became the punishments of choice. Prisoners sentenced to transportation needed to be held somewhere whilst awaiting a transport ship.

The problem of holding the prisoners before embarkation however was solved by using the hulks. The hulks were unusable fighting ships that were moored in the Thames, the Medway and at Portsmouth. Prisoners were placed in these hell holes that were rotten, rat infested, filthy, verminous, overcrowded and demoralising. When the prisoners were not working they were placed in irons.

Sentences were for 1, 7, 14 years or for life. Children as young as 9 years old as well as females were placed in these ships. The prisoners were used to raise gravel, soil and sand from the Thames and other navigable rivers and also gave assistance at the dockyards. In such overcrowded places disease was rife and cholera and typhus were ever present

Malcolm Byard

Prisoners were held on the hulks from 1776 and most were sentenced to hard labour. The hulks were intended as places to hold prisoners before they were punished in other ways but became a form of punishment in themselves. Hard labour was meant to help reform criminals by teaching them to be industrious, but the threat was also meant to deter others from committing crime. But this was not intended to be a long-term solution. Even so, hulks played a vital role for many decades and the last prison hulk was still in use in Bermuda in 1864. Men imprisoned in the hulks worked on dredging the Thames or in the naval dockyards.

Others were put to work on ballast lighters (vessels which conveyed debris, sand and silt from the beds of rivers).

Transportation in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Transportation to territories which are now in the USA and Canada ceased on the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). In the early 1780s, a small number of prisoners were transported to West Africa to man the slave forts…stopovers for slaves during the transatlantic slave trade. Anti-slavery lobbying and the high mortality rate of prisoners and guards eventually put a stop to that.

The late 18th century brought a huge increase in the use of transportation as a means of removing convicts from view and using them as free labour. From 1787, transportation to Australia and Van Diemen’s land began in earnest.

Once arrived in Australia, convicts lived in barracks and worked at stone-breaking, building roads and bridges or farming the land. Many remained voluntarily once they were freed and made better lives for themselves than they could in Britain.

The policy of transportation reflected two trends in punishment regimes. There was a movement away from corporal punishments and towards incarceration and there was a movement towards removing convicts to places out of the public eye. More than 165,000 prisoners were transported to Australia until transportation was abolished by the Penal Servitude Act of 1857 when prison became the substitute for all transportation sentences.

Crime and Punishment in the 19th Century

A huge growth in Britain’s population, combined with both agricultural and industrial revolutions, led to an enormous increase in crime in the first part of the 19th century. Most crimes were property related, i.e. petty theft, robbery, burglary, receipt of stolen goods and pick-pocketing. Of course many crimes were caused by greed but they were also associated with deprivation, drunkenness, poverty and despair.

In the late Georgian and Victorian periods, criminals were usually punished by periods of imprisonment with or without hard labour, transportation to a penal colony in the Southern Hemisphere, or execution. By 1815, a staggering 225 crimes carried the death penalty. However, many reformers felt that sentences were too harsh and judges began to commute sentences of death to transportation or imprisonment.

In 1823, Sir Robert Peel’s government reduced the number of offences for which convicts could be executed by over 100. Peel’s Metropolitan Police Act 1829 established a full-time, professional and centrally-organised police force for the greater London area and provincial forces followed with organised police forces, replacing the parish constables. In 1830, Lord John Russell abolished the death sentence for horse stealing and housebreaking…and by 1860, crimes attracting the death sentence had been reduced to only four…murder, treason, piracy, and “arson in naval dockyards”. Victorian Justice records show there were still some severe sentences, such as:

- A woman received a sentence of five years in gaol for stealing one rasher of bacon.

- In 1842, when he was 14 years old, a boy named Henry Catlin was sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for 14 years. He had stolen 3 shillings and sixpence.

- An agricultural labourer named John Walker was convicted of the theft of onions valued at between 4 and 5 shillings. He was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude and seven years’ police supervision.

- A woman who was sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment with hard labour in 1875 for procuring abortions.

- A 19 year old girl given five years of hard labour in prison and seven years of police supervision for stealing an umbrella.

The abolition of transportation required many more prisons to be built to cope with the increasing numbers of prisoners. Existing prisons were unhealthy and overcrowded and sometimes housed in old buildings, such as castles. Some were the old “Houses of Correction”. They each held a mixture of men, women and children, some awaiting trial, those under sentence of death, along with debtors and some minor offenders, all without any privacy or protection.

Houses of Correction

We need to go back in time, now, to look at the provision of Houses of Correction (think Doctor Who and time travel). An Act of Parliament in 1576 had required Justices of the Peace to provide Houses of Correction, to deal with vagrancy, in the areas of their jurisdiction and all English towns had to have one by 1609. Vagrancy refers to people who lived and begged on the streets, who were without visible means of support and without a permanent home. It was a growing problem in the 16th century. Some of the causes were:

- unemployment caused by slumps in the cloth industry;

- land being enclosed for sheep farming thus depriving tenants of their rented land;

- inflation due to taxation to pay for foreign wars;

- the increase in unemployment following the dissolution of the monasteries;

- increasing population.

Many people thought that the vagrants were criminals, or might carry the plague, or might be likely to rise up in rebellion…and they felt threatened…leading them to treat the vagrants and beggars very badly. The Tudor Beggars Act in 1531 allowed:

If any man or woman being whole in body be vagrant and can give no explanation how he lawfully gets his living, he shall be tied to the end of a cart, naked, and be beaten with whips throughout the town till his body be bloody. He shall then return to the place where he was born.

Key Writings on Subcultures, 1535-1727 Vol 1

A second offence entailed the loss of one ear and the third offence incurred the loss of the remaining ear. The law changed in 1547, replacing the 1531 legislation. Now, anyone unemployed for three days was termed a vagrant, and could be offered work – if work was refused, the vagrant was branded with a ‘V’ on the breast and given as a slave for two years to the person who reported him. If a slave ran away twice he could be executed. Children youths and girls who were forcibly enslaved were apprenticed then deemed to be their master’s personal property. In 1572, vagrants should be whipped and bored through the ear for a first offence and executed for a third offence.

The purpose of the 1576 Act requiring the provision of Houses of Correction was to provide work for vagrants and also for the so-called “sturdy beggars”, harlots and idle apprentices, who “might be corrected in their habits by laborious discipline”.

The West-Riding (Wakefield) House of Correction

The first Wakefield House of Correction (H of C) was endowed in 1595 from the will of barrister George Saville…and built two years later, probably on the site of the present prison. There were already two prisons in Wakefield, the old manorial gaol, near the cathedral and one at Sandal Castle, but Houses of Correction were different to those in two ways:

1. Governors of the Hs of C were paid a salary by the local magistrates, £80 was the initial annual stipend for the governor of the Wakefield H of C plus any benefits from the sale of prisoners’ work. An Act of 1597 made justices responsible for paying the governor and employing the staff. Governors of gaols were not salaried, they made their money from charging the prisoners for their keep and unlocking their irons on release and also selling the prisoners’ work. The more a prisoner paid (or his relatives) the better his conditions and treatment. This payment was abolished in an Act of 1773.

2. The occupants of the H of C had committed no crime, at least none for which there was a punishment; they were ‘sturdy beggars,’ vagrants, and idlers.

Malcolm Byard

In time, the Wakefield H of C started to hold prisoners awaiting trial or, after trial, awaiting punishment and eventually became a prison used for accommodating prisoners on custodial sentences.

Here we go round the mulberry bush

There is a belief that the song “Here we go round the mulberry bush” originated with female prisoners at Wakefield Prison. A sprig was taken from Hatfield Hall in Stanley, Wakefield, which grew into a fully mature mulberry tree around which prisoners exercised in the moonlight.

Here we go round the mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush.

Here we go round the mulberry bush

On a cold and frosty morning.

This is the way we wash our face,

Wash our face,

Wash our face.

This is the way we wash our face

On a cold and frosty morning.

This is the way we comb our hair,

Comb our hair,

Comb our hair.

This is the way we comb our hair

On a cold and frosty morning.

This is the way we brush our teeth,

Brush our teeth,

Brush our teeth.

This is the way we brush our teeth

On a cold and frosty morning.

This is the way we put on our clothes,

Put on our clothes,

Put on our clothes.

This is the way we put on our clothes

On a cold and frosty morning.

Here we go round the mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush,

The mulberry bush.

Here we go round the mulberry bush

On a cold and frosty morning.

The main sources of information for the Wakefield H of C are the court records. The records show that repairs and additions were made to the prison, that it was inspected regularly and that care was taken in appointing suitable gaolers and governors (turn-keys and masters). It would have been little different from any other provincial gaol where overcrowding, disease and insanitary conditions prevailed. Men and women shared the same facilities and were kept in leg irons. When being taken to appear at the Quarter Session courts they were marched in groups of up to 50 or more and walked up to 35 miles each way in neck fetters.

The building eventually fell into poor repair, facilitating a large escape of prisoners in 1752. This led to plans being drawn up for a new building, which was completed in 1766 and the building of a separate women’s prison in 1770. The prison reformer, John Howard visited Wakefield in 1774 and wrote:

WEST RIDING WAKEFIELD. This prison is unfortunately built upon low ground; so it is damp and exposed to floods. Four of the wards are spacious, but all the wards are made vary offensive by sewers. Prison and Court are out of sight from the keeper’s house, though adjoining; and some prisoners have escaped. They are now let out to the Court only half an hour in the day. The wards are dirty. A prison on ground so low as this requires the utmost attention to cleanliness.

John Howard, Prison Reformer

Gradually conditions improved somewhat, with the provision of separate cells, lime-washing of all walls and ceiling and fumigation of prisoners’ clothing on admission. All prisoners were required to wash their face, hands and head with soap, daily…and male prisoners were to be shaved “as often as might be proper”.

Elizabeth Fry the great prison reformer, visited the Prison in September 1818. Although she found “the whole prison very cleanly”, there was gross overcrowding and disorder. Observing the “evening association” from six to eight pm she wrote:

This period as well as most of the Sabbath Day is devoted to noise, jollity and mischief. We were introduced to the felons’ day room during the evening. Hours of riot and confusion, it was crowded to excess; and never have we seen a company of prisoners more marked by the appearance of turbulence and desperation.

Elizabeth Fry , Prison Reformer

At this time the weight of the leg irons was increased in accordance with the severity of the crime committed. Punishment schedules could involve solitary confinement in a dark cell and being fed only food and water…periods of three days in a dark cell might be used in rotation with time in the prisoners own cell on only bread and water, and time in his own cell on regular diet. Prisoners under sentence of hard labour might be put on “the crank”, “the treadmill” or be made to work on stone-breaking or oakum picking.

In 1878 the Wakefield H of C came under the Prison Service in the control of the Home Secretary and was re-named “Wakefield Prison”. At this time, most prisoners were serving relatively short sentences for minor offences.

Rothwell Debtors’ Gaol for the Honour of Pontefract

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and six pence, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

Charles Dickens in “David Copperfield”.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries more than half of all prisoners were debtors. Those who were in debt and could not pay could be sent to the debtor’s prison and would have to stay there, for an indefinite period, until they had worked off their debt. The payment for their work done in prison went to the cost of imprisonment and the residue to pay off their debt, unless they found another way to pay, for example, donations from family or charitable organisations. The creditor had to be repaid in full before the prisoner could be released but this was easier agreed than it was achieved.

Until the law changed in 1815, debtors could be worse off after a few years in prison than when they entered. Sometimes the small amounts that they could earn from prison work didn’t even cover their keep, so they had no way of ever getting out of debt and being discharged from prison.

In Victorian Britain, the concept of debt was related to a person’s character and the moral standards of the time. So being in debt was seen as a moral failure and was punished accordingly. Working class people, seen to be failing to pay their debts, were punished more harshly than the upper classes who were dealt with more leniently, because the upper class debtor might be viewed to have suffered misfortune…whereas the working classes were thought to be deliberately and maliciously avoiding payment. Declaring bankruptcy was a way of avoiding prison, but the bankruptcy declaration cost £10, several months’ pay for a working man, so an individual who could not raise that £10 must submit to incarceration….and until 1861, only the merchant class could declare bankruptcy anyway.

The Debtors’ prison was established in Rothwell, Leeds, in the seventeenth century and was later converted into a workhouse. When debtors were first taken there, the Society of Debtors demanded that each newcomer pay a “garnish” or fine of half-a-crown (2 shillings and sixpence) or forfeit his coat. A prisoner committed to Rothwell Gaol for 40 days in 1842 complained:

I have nothing in the world to eat or drink, I get a little out of charity from the other debtors. I brought in 3s 6d with me: I had to pay 2s 6d out of it for garnish; if I had not paid it I should have had my coat taken. The keeper states that he has made many applications on behalf of destitute prisoners to their parishes for support, but has invariably been refused.

In workhouses.co.uk

Rothwell gaol had its own song too

We bid you welcome, brother debtor, to this poor but nary

place,

Where no bailiff, bum or satyr dare to show his frightful face.

Now, kind sir, as you’re a stranger down your garnish you

must lay,

Or your coat will be in danger, you must either strip or pay.

Ne’er repine at your confinement, from your childer and your

wife,

For wisdom lies in true resignment, through the varied scenes of life.

What was it made great Alexander weep at his unhappy fate?

It was because he could not wander through this wide, strong prison gate.

Every island is a prison strongly guarded by the sea.

Kings and princes for that reason prisoners are as well as we.

York Castle Prison

York Castle, built in 1068 by William the Conqueror, was used as a prison for almost 1000 years. It still has holding cells which are used to hold prisoners accused of serious crimes, who are awaiting trial and the 18th century courthouse is now used as York Crown Court. The prison has housed some of Yorkshire’s most notorious criminals, such as the convicted highwayman Dick Turpin.

Originally, debtors were housed on the top floor and those convicted of felony at the bottom, where conditions were worst. Conditions became unbearable as the prison become more overcrowded…filthy and prone to disease. In the early 18th century, a separate debtor’s prison was built, described as ‘the most stately and complete of any in the kingdom, if not in Europe’.

Prisoners had to somehow find payment for their bed and food whilst awaiting trial. Convicted felons were mostly transported or hanged.

During the 19th century, separation of male, female and juvenile prisoners became common as did separating prisoners based on the severity of their crimes.

Family Case Histories

George Archer

I have reported elsewhere, and in detail, the case of my five times great grandfather who was arrested on serious charges relating to what we might now call industrial espionage. His textile machine building business had failed in 1802. George’s pecuniary misfortune was reported in the bankruptcy pages of the London Gazette and The Leeds Intelligencer in April 1802:

George Archer’s Assignment

Whereas George Archer, of Ossett, in the Parish of Dewsbury, in the County of York, Machine Maker, hath by Indenture bearing Date the First Day of April Inst. assigned over all his estate and Effects unto certain Trustees therein named, IN TRUST, for the benefit of such of the Creditors of the said George Archer as shall accede to and execute the said Assignment on or before the Fifth of June next.

NOTICE is therefore hereby given,

That the said Assignment is lodged at Mr Rylah’s Office, in Dewsbury, for the Inspection and Execution of the Creditors of the said George Archer; and such of them as shall not execute the same within the Time aforesaid, will be excluded the benefit thereof.

All Persons indebted to the said George Archer, must immediately pay their respective Debts into the Hands of the said Mr. Rylah, otherwise Actions will be commenced for the Recovery thereof. Dewsbury, April 2nd, 1802

George avoided debtor’s prison, but was inevitably living in much reduced circumstances when his brother-in-law Henry Dobson arrived from France for a visit in 1803 and this connection would lead George into further trouble. The full story of the entanglement that led to George’s arrest and conveyance to York Castle prison is told at this link.

George was fortunately acquitted and shortly afterwards he fled to the USA, but his accused co-conspirator, Henry Dobson, was found guilty of “seducing artifices out of the kingdom” and was fined a sum of £500 and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment. He was then tried at Pontefract for “Taking models of manufacturing machinery for the purpose of introducing abroad”, found guilty, sentenced to another year of imprisonment and fined another £200. There is also a record of Henry Dobson of Ossett, “ironfounder”, being imprisoned at York Castle Debtor’s Prison in 1804. On his release it is said that Dobson returned to France.

John Archer (George’s son)

John Archer was my 4x great grandfather. He had eleven children with two wives. His first wife died at the age of 30 in 1806, when their fourth child was an infant.

John had been given a reward of £100, in 1803, for evidence leading to the arrest of his father George, and of Henry Dobson and he had set up as a textile machine maker in Batley, West Yorkshire. In 1814, John was in possession of two closes of land situated in Ossett and in 1820 he acquired land at Little Stotts Close in Batley, where he built a “cottage and shop” (possibly a workshop). He appears to have been doing quite well in his business at this time.

However, like his father, it seems that John’s business eventually failed. I found a record showing that John signed a release of the land in Batley in May 1840. Perhaps he was already in financial trouble then and very soon afterwards his finances were in a very bad state. There is more research to do here, but I do know that, at the 1841 Census, John was recorded as being a resident of Rothwell Debtors’ Gaol. He died thee years later.

Robert Archer (John’s son)

Robert Archer was my 3x great grandfather. Robert was a textile engineer like his father and grandfather, though he did not have his own business. In 1846, at the age of 31, Robert was working for George Pollard, Machine Maker, of Horbury. On 31st January 1846, the “Leeds Intelligencer” reported that Robert Archer, of Dewsbury, was charged with stealing a quantity of tools from his master, George.

The prosecutor had missed tools at various times and on searching the prisoner’s house, a considerable portion of the stolen articles were found.

Robert was committed to the Sessions. He was tried on 2nd March 1846. It was reported in the Leeds Times on 7th March that Robert Archer was acquitted of stealing a quantity of joiners tools, at Horbury, the property of George Pollard.

Robert did go on to lead a successful life, working as a textile engineer and later leasing land on which he built four houses, two for his family and two to rent out. But in later life he had mental health problems and he died in Wakefield Lunatic Asylum and is featured in my story “Are You Mad?“.

Smith Archer (Robert’s son)

Smith was my 2x great grandfather. He married an innkeeper’s daughter and took over the British Oak public house in Earlsheaton (Dewsbury). Smith was charged with receiving stolen property comprising five rugs, the property of John Illingworth, at Heckmondwyke, on 8th February 1882. (Where better to offload stolen goods than at a pub?). The men accused of stealing the rugs were Abraham Stubley, aged 51, Engine tenter and Thomas Field, 38, Collier. Both had previous convictions. Smith was remanded on bail, the others in custody and the case came before the Magistrates on 8th April 1882. Field was found guilty and imprisoned for 18 months. Stubley and Archer were acquitted.

It is likely that Smith’s public house was already not doing well, because very soon afterwards, Smith was declared bankrupt:

The Bankruptcy Act, 1869.

In the County Court of Yorkshire, holden at Dewsbury. In the Matter of Smith Archer, of the British Oak Inn, Middle-road, in Dewsbury, in the county of York, Beer-house Keeper, a Bankrupt. Walter Dawson, of Dewsbury, in the county of York, Accountant, has been appointed Trustee of the property of the bankrupt. The Court has appointed the Public Examination of the bankrupt to take place at the County Court-house, Dewsbury aforesaid, on the 14th day of June, 1882, at ten o’clock in the forenoon. All persons having in their possession any of the effects of the bankrupt must deliver them to the trustee, and all debts due to the bankrupt must be paid to the trustee. Creditors who have not yet proved their debts must forward their proofs of debts to the trustee—Dated this 22nd day of May, 1882.

London Gazette 26th May 1882

Smith was 37 years old, a bankrupt, who would have been forced to quit the public house which was his home as well as his business, and already had the first six children of ten to support. Smith’s situation did not improve and he was soon in trouble again…on 30th June 1884, at the Quarter Session at HM Prison Wakefield, he was found guilty of stealing three pewter measures and a pair of scales and sentenced to imprisonment for three months at Wakefield.

On 23rd March 1885 Smith was further convicted of non-payment of the poor rate (today’s equivalent would be council tax) and given 14 days to pay £2 8s 0d (2 pounds and 8 shillings).

Smith gave up on running his own business and became employed in the mill. In 1891 he was a rag extractor and in 1901 he worked as a spinner in a woollen mill. There is no evidence from the census that his wife ever had paid work, so he must somehow have managed to support his large family. But Smith’s life in some ways did not improve as he was committed to Wakefield Lunatic Asylum for a short time in 1895, when he was 50 years old. He had a wife and ten children by then, the youngest of whom was barely four years old and Smith is featured in my story “Are You Mad?“.

Sarah Ann Archer (Smith’s sister)

The 1880s was not a good decade for the Archer family. One way to avoid the debtor’s prison was to escape abroad. Only months before Smith’s bankruptcy, Sarah Ann, his sister, had become involved with a married man who also had serious debts. The Leeds Mercury reported on 20th August 1881:

A strange elopement from Dewsbury

Within the last few days it has been discovered that George Crosland, who was formerly a member of the Dewsbury Borough Police Force, and subsequently a warehouseman at the works of Messrs. B. Hepworth and Sons, New Wakefield Mills, Dewsbury, and who had the reputation of being a respectable man, has eloped with a young woman named Sarah Archer, the daughter of a mechanic working at the same place. Crosland has two children, one being almost at the point of death, and his wife also is in a state of delicate health. For about five months, owing to a severe illness, she has been confined to her house.

Crosland engaged in trade on his own account, and latterly he extended his operations, and becoming acquainted with a wholesale jeweller in Leeds, from whom he bought watches and chains, for a time paid him with regularity. With this firm, he is about £400 in debt. He has also obtained goods from tradesmen in Dewsbury, among them being Mr Hodgson, jeweller, to the amount of £70. He is behind in his accounts with the Conqueror Lodge of the Independent Order of Oddfellows, of which he is the Treasurer, to the extent of £8. Mr Hodgson, through the exertion of Detective Whittel, has secured the greater portion of his property, which had been pawned at various places by Crosland.

It has been ascertained that Crosland, some days prior to his departure, called upon Mr J. Carter, accountant and emigration agent, Dewsbury, and obtained tickets on board the steamship England, of the National Line, saying he wanted them for a married couple who were friends of his, and he paid for saloon tickets. On the pretence of going to Blackpool, (Sarah Ann) Archer went to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Station at Dewsbury and booked for Manchester, and then proceeded to Liverpool, where the pair embarked on the steamship England as Mr. and Mrs. Walker, aged 37 and 30. Archer is single and 23 years of age; but she is the mother of a child of 2 years old, which she has deserted. Much sympathy is expressed for Mrs. Crosland and her family.

Sarah Ann was back in Dewsbury giving birth to a second illegitimate child in 1886 but later married and settled down, living to the age of 79. The child of two years whom Sara had deserted won a scholarship to Batley Grammar School, went on to become a prosperous and highly thought of member of the community and a director of a Building Society in the North Midlands. He bought a group of weekly newspapers and later also became managing director of a south coast newspaper.

Epilogue

I think that there is some evidence that the petty criminality of some of my family members in the 19th century was tied up with both money troubles and possibly also with mental health issues. Maybe one contributed to the other. It is no doubt inappropriate to apportion blame for their actions as we do not understand, at this distance and without much more information, what drove them to break the law. My hope is that their encounters with law enforcement were as few as I have found and that they were deterred from further unlawful actions.

I do know that the next generations, my great-grandfather, grandfather and father were honest, hard working and law abiding citizens. They were loving parents and brought up their children with kindness and a respect for the law.

© Christine Widdall Jan 2019. I am indebted to Malcolm Byard for sharing his research on crime and punishment with me.