Civil War Years 1644-49

The Battle of Sowerby Bridge…and the fate of Heptonstall

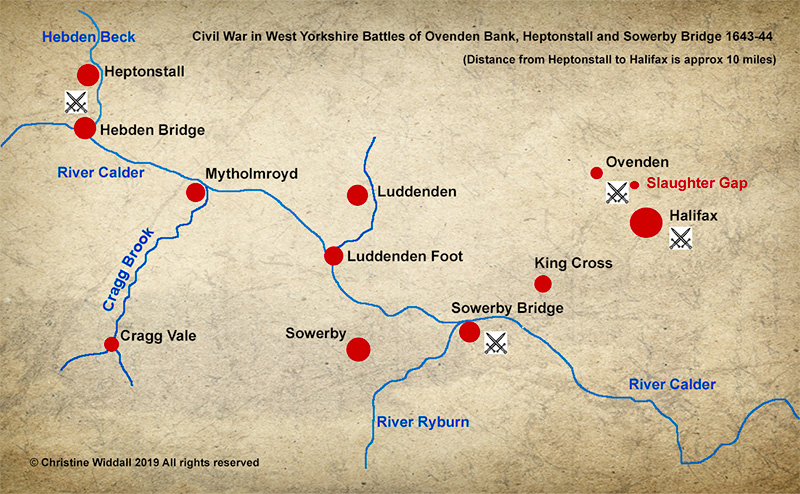

On 4th January 1644, Major Eden marched a force of 600 men from Heptonstall to Sowerby, intending to attack the village of Sowerby Bridge at the bottom of the hill. The Royalists defended the bridge bravely in hand-to-hand fighting, but the bridge and 42 prisoners was taken. Three Royalist soldiers were killed. Dividing his forces, some of Eden’s men demolished Sowerby Bridge’s defences, while the other part, under Captain Farrer, pursued the defeated Royalists as they fled towards Halifax.

But Farrer pursued too far and found himself behind enemy lines. Farrer and his men then attempted to go around to the north-west of Halifax via Ovenden Woods towards Luddenden Dean, planning to cross Midgely Moor on the way back to Heptonstall. However, it was difficult terrain for the horses and the Parliamentarians were pursued and intercepted by Royalist Cavalry from King Cross. Farrer decided to make a stand and fighting occurred on the slope between Hunter Hill and Mixenden Brook at a place in Binns Hole Clough, known as “Slaughter Gap”.

Approximately a hundred men were involved in the combat and eventually the Royalists prevailed, taking ten prisoners, including Captain Farrer and killing one soldier. Those of Farrer’s soldiers who evaded capture fled to the safety of Heptonstall, while Farrer and the other captured men were imprisoned in Halifax.

At Halifax, two of Farrer’s captured men were recognised as being deserters from Mackworth’s army. They were quickly condemned to death and were hanged on a gallows erected near Halifax Gibbet. Two more of the captured soldiers died from their wounds, at Halifax, over the following days.

On 9th January 1644, Sir Francis Mackworth led a force of more than 2,000 men to punish the Parliamentarians garrisoned at Heptonstall. Vastly outnumbered, Eden realised that retreat was the only possibility, so he abandoned Heptonstall and retreated towards Lancashire. His route would have taken him through Blackshaw Head, across the “Long Causeway” and over the moors until they reached Burnley and Colne. Eden and his troops were given new orders re-join Thomas Fairfax’s main army. Meanwhile, the Royalists marched unopposed up the Buttress, from Hebden Bridge into Heptonstall, where they razed to the ground fourteen houses and barns, which would have contained the looms, fleeces and cloth of the clothiers. This action would have reduced them and their families to penury and possibly starvation.

On 28th January 1644, after seven months of bitter fighting in the area, Mackworth was ordered to completely abandon Halifax, as his force was urgently needed to help to oppose the advance of Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell.

1644 Parliamentarian Pact with the Scots

With the Royalist armies occupying themselves in Lincolnshire, the Fairfaxes sought re-inforcements and made a pact with the Scottish Covenanters.

The signing of the Solemn League and Covenant between Parliament and the Scots and the subsequent Scottish invasion of England marks a major turning point in the English Civil War. The Scottish Government agreed to provide an army of 18,000 foot, 2,000 horse and 1,000 dragoons to fight against the Royalists, giving a strong military advantage to Parliament.

http://bcw-project.org/military/english-civil-war/northern-england/the-north-1644

Scots, under the Earl of Leven, occupied Berwick-on-Tweed in September 1643 and, on 19th January 1644, Leven ordered his troops to cross the Tweed and advance south into England. Leven advanced cautiously southwards through Northumberland but encountered little opposition. Sir Thomas Glenham, the Royalist Governor of Newcastle, had insufficient forces to challenge the Covenanters.

Death of Sir William Savile, 3rd Baronet, of Thornhill (1612 – 24 January 1644)

Sir William Savile of Thornhill died near York, in fighting, on or around January 22nd 1644. He was 31 years old and was buried at Thornhill, Dewsbury, in the church next to his home. His widow, Lady Anne, reporting his death to Major Beaumont at Sheffield Castle said:

I cannot expresse ye sorrow I have for the losse of your noble Colonell…

From a letter from Lady Anne Savile to Major Beaumont at Sheffield Castle

The grieving Anne, who was pregnant with William Savile’s seventh child, continued to work for the Royalist cause and took her existing six children to part of the Savile Estate at Rufford Abbey in Sherwood Forest and later took refuge in Sheffield Castle.

Anne had married Sir William Savile on 29 December 1629, when he was 17 years old and she probably even younger. After having seven children with Sir William, Anne went on to marry Sir Thomas Chicheley in 1655, ten years after Williams death. As Lady Thomas Chicheley she then had another two sons. She died in 1662.

Bradford, Ferrybridge and Selby, March/April 1644

On 3rd March 1644, Colonel Lambert finally drove the Royalists out of Bradford and established the town as a base for raids in the West Riding.

On 25th March, Royalist Belasyse, who had now moved his HQ from York to Selby, made a cavalry attack on Bradford, which almost succeeded. As had happened before, the defenders were quickly running out of ammunition and, in a desperate and bold move, Colonel Lambert broke out of the town and overwhelmed the Royalist cavalry, allowing Lambert to return to Bradford to secure it, while Belasyse withdrew to Selby.

The Yorkshire Parliamentarians now planned an assault against Selby. At Ferrybridge, near Wakefield, the two Fairfaxes, father and son, joined force with troops from Hull, Bradford and the Midlands. Their combined forces amounted to 1,500 cavalry and 1,800 foot soldiers. On 11th April 1644, they attacked Selby from three sides at once, completely overwhelming Belasyse’s Royalists. Most of the Royalist cavalry escaped, but about 1,600 foot soldiers were taken prisoner. Belasyse himself was wounded and captured.

These events were potentially disastrous for York, which now had only two Royalist regiments defending the city. The Earl of Newcastle, pursued by the Covenanter army, abandoned his campaign against the Scots invasion and withdrew his forces to York, to strengthen its defence.

The Siege of York, April-July 1644

At Thormanby on 16th April, Leven and his Scottish Covenanters marched via Boroughbridge to rendezvous with Lord Fairfax and the Yorkshire Parliamentarians at Wetherby. The combined “Army of Both Kingdoms” arrived outside York on 22nd April 1644 and set siege to the city. However, taking York seemed impossible, as the city was so well defended. The medieval city walls had been repaired and strengthened and earthworks had been constructed beyond the walls. Each of the town gates was defended by cannons.

The Scots occupied the sector west of the city, the Fairfaxes that to the east…but the sector to the north between the Ouse and Foss was left open, so the defenders were able to get some supplies into the city and mount a few raids outside the walls. During this time, the Parliamentarians took Stamford Bridge on 24th April and Cawood Castle on 19th May, consolidating their position in Yorkshire

On 3rd June 1644, the Northern Association and Covanenters were joined by the Eastern Association, under the Earl of Manchester, with Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell’s “Ironsides”. The Eastern Association had lately secured Lincolnshire for the Parliament and now they guarded the sector to the north of York, between the Ouse and Foss, cutting off the defenders’ route for supplies.

The Parliamentarians now were able to take several more small Royalist garrisons nearby, such as Crayke Castle.

During this time, Prince Rupert was recruiting forces in Lancashire and Wales in preparation for attacking the Parliamentarians outside York, who were now bombarding the walls and attempting to storm the city.

Advancing through the north west, Rupert stormed Stockport and Bolton. At Bolton, the Royalists massacred at least 1000 Parliament forces and citizens, said to be in retaliation for the hanging of several Royalist prisoners. Rupert then advanced through Lancashire, crossed the Pennines and reached Skipton Castle on 26th June, with an army now numbering 15,000.

On hearing that Prince Rupert was on his way from Skipton with major reinforcements, the besiegers lifted the siege of York and their three armies came together at Hessay Moor, west of York. The speed and ruthlessness of Rupert’s advance had left them undecided whether to retreat or stand and fight and they prudently moved further off towards Long Marston, a village situated between York and Wetherby, intending to draw off further towards Tadcaster. However, the Parliamentary rear guard held by Oliver Cromwell and Tom Fairfax were soon engaged by Rupert’s advance troops and his main force was only a mile away. The Allies therefore halted at a place known as Marston Moor, from where urgent messages were sent to recall the infantry, who had already moved on towards Tadcaster.

The Battle of Marston Moor

Tuesday 2nd July 1644

Let’s set the scene in Thomas Fairfax’s own words:

Soon after, Prince Rupert came to relieve the town. We raised the siege and Hessay Moor being appointed the rendezvous, the whole army drew thither, about a mile from where Prince Rupert lay, the river Ouse being between us which he, that night, passed over at Poppleton…

…We were divided in our opinions what to do; The English were for fighting, the Scots for retreating, to gain (as they alleged) both time and place of more advantage. This being resolved on, we marched away to(wards) Tadcaster, which made the enemy advance the faster….

Lieutenant-General Cromwell, Lesly and myself…sent word to the generals of the necessity of making a stand…

The place was Marston Fields, which afterwards gave name to this battel. Here we drew up our army.

From: “A Collection of Scarce and Valuable Tracts on the Most Entertaining Subjects…Tracts during the Reign of King Charles I”, By Sir Walter Scott

Rivalries between the Royalist commanders now got in the way of the battle’s progress. Prince Rupert intended a rapid attack, but he was held back by Newcastle, whose forces only joined Prince Rupert at Marston Moor on the morning of 2nd July and by James King (Lord Eythin), who was slow to bring up the infantry from York. There was no love lost between James King and Rupert after they had fallen out over the battle of Vlotho, six years before, so he was slow to obey orders. Prince Rupert and the now “Marquis” of Newcastle now disagreed about when to make their attack and how to interpret the King’s orders.

This delay was fatally damaging to the Royalists, as it gave the Parliament forces more time to retrieve their infantry and make preparations for battle. The Royalist lines of battle were not drawn up until late in the afternoon of 2nd July and the two armies didn’t engage until 7 pm, the Parliament led by the Earl of Leven and the Royalists by Prince Rupert.

Much has been written elsewhere about the Battle of Marston Moor, so it will be only briefly described here. This battle is believed to have been the largest battle ever fought on English soil. The Royalist forces, numbering about 18,000 men, engaged with Yorkshire Parliamentarians, Scottish Covenanters and Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell’s Eastern Association and his infamous “Ironsides”. The combined armies on the Parliament side numbered about 28,000 men. Lord Fairfax took the centre with the Earl of Manchester; Oliver Cromwell took the left flank and Sir Thomas Fairfax, the right flank.

In just a couple of hours on Marston Moor, the fate of Yorkshire and the control of the whole of the North was to be decided. After initial Royalist success, the tide of the battle turned. Cromwell and his Ironsides broke through the Royalist army’s right flank and were able to engage them from behind. Prince Rupert was defeated and the Royalist Northern Army was effectively destroyed. All the Royalist ordnance, gunpowder and baggage were captured and almost all of Newcastle’s regiment of Whitecoats were killed. The Royalists lost 4,000 killed and 1,500 captured. Incredibly, Parliament lost only 300 men.

Prince Rupert, with survivors of his army, retreated to Chester to begin to recruit, but the defeat at Marston Moor had broken the power of the northern Royalists and they abandoned most of their positions in the North of England. York surrendered two weeks later. After the surrender of York, only a few isolated Royalist strongholds remained in the north, including Pontefract Castle, and the main focus of the First Civil War moved way from Yorkshire to the south and west of England.

The Battle of Marston Moor also made the name of Oliver Cromwell as a great commander and showed how a well-equipped, trained and determined Parliamentarian army could win the war, though, to be fair, they also had the advantage of 10,000 more troops on that occasion!

The Marquis of Newcastle was encouraged by Lord Eythin, to go into exile, and lived at Hamburg from July 1644 to February 1645 before moving to Paris where he joined Queen Henrietta Maria’s court-in-exile. Eythin exiled himself to Sweden, where he died in 1652.

Recapture of Sheffield Castle

In August 1644, 1200 Parliamentary soldiers under the Earl of Manchester were sent to re-capture Sheffield Castle. Finding their cannon unable to breach the walls, they sent for a demi-cannon called “The Queen’s pocket pistol” for close distance bombardment and also a “whole culverin” which was used to bombard targets from a distance. During the bombardments, Sir William Savile’s widow, Anne, gave birth to their seventh child, Talbot, at the castle.

She gave a gallant and warlike defence to the battering from guns on all sides, in spite of her advanced pregnancy. Against her orders, the garrison eventually surrendered the crumbling castle and she gave birth the same night on 11 August 1644.

Wikipedia

Pontefract Castle

When the Civil War began, Pontefract Castle was held by supporters of the King. The castle had dominated northern England for 500 years and housed the Royal Armoury in Yorkshire. It was considered to be impregnable and became a key stronghold in West Yorkshire during the war…from there, Royalist forces could set out to attack the clothing towns held by Parliament.

The castle remained in Royalist hands and proved impenetrable when Parliament troops, under Sir Thomas Fairfax and Col Lambert, laid siege on Christmas Day 1644. By the 22nd January 1645, 1367 cannon shots had been fired at the castle but still only one small tower was destroyed. Parliamentarians then tried to mine under the castle, but it was built on solid rock and it was impossible to break through. A second siege began on the 28th March and eventually the occupants were starved out in June 1645.

On 3rd June 1648, Royalists under Captain W Paulden and Colonel Morris entered the castle in disguise. They surprised the defenders and seized control. Oliver Cromwell was now ordered to re-take it.

In November 1648 Cromwell visited Pontefract and wrote a letter to the House of Commons, from nearby Knottingly, dated 15th November 1648, explaining why it was so difficult to take…

My Lords, the castle hath been victualled with Two-hundred and twenty or forty fat cattle, within these three weeks; and they have also gotten in…salt enough for them and more. So that I apprehend they are victualled for a twelvemonth.

The men within are resolved to endure to the utmost extremity; expecting no mercy, as indeed they deserve none. The place is very well known to be one of the strongest inland Garrisons in the Kingdom; well watered; situated upon a rock in every part of it, and therefore difficult to mine.

The walls are very thick and high, with strong towers, and if battered, very difficult of access, by reason of the depth and steepness of the graft.

Oliver Cromwell’s letters and speeches

Cromwell went on to say how greatly impoverished Yorkshire had become and that it was not unable to freely quarter the army nor provide food for the soldiers, therefore he requested…

(sic)…That moneys be provided for Three complete regiments of Foot, and two of Horse; that money be provided for all contingencies which are in view, too many to enumerate. That Five hundred barrels of powder, Six good Battering-guns with Three hundred shot to each Gun, be speedily sent down…we desire that none may be sent less than demi-cannons. We desire also some match and bullet. And if it may be, we should be glad of two or three of the biggest Mortar-pieces with shells may likewise be sent.

Cromwell as a Soldier – Thomas Stanford Baldock

However, Cromwell did not take Pontefract. He was recalled to London on other business, the trial of King Charles I, leaving Lambert to finish the siege. Pontefract was the last Royalist stronghold to hold out but the occupants eventually realised the futility of their situation and the castle finally surrendered on 24th March 1649.

Sandal Castle

Sandal Castle near Wakefield was one of two castles built to defend crossing points of the River Calder. It was already in a neglected state at the beginning of the Civil War, when Royalists occupied and garrisoned it.

In 1645, manpower and artillery were sent to Sandal and it was besieged three times that year by Parliamentary troops, until the small garrison of ten officers and 90 men eventually surrendered the castle on 1st October 1645. Their store of 100 muskets, 50 pikes, 20 halberds, 150 swords and two remaining barrels of gunpowder were seized.

Sandal was one of the last Royalist castles in Yorkshire to hold out, with only Bolton Castle and Skipton Castle remaining in Royalist hands, though Pontefract was to be re-taken three years later. Between 1646 and 1648 Sandal Castle was systematically demolished. Today it is a complete ruin, though the motte (mound on which the keep was built), a few fragments of wall and the deep ditches remain. From the top of the motte to the west can be seen the river and the view towards Emley.

Below: Sandal Castle Ruins, May 2019

New Model Army – Battle of Naseby

The Parliamentarians became divided about the conduct of the war. Some wished a reconciliation with the King, while the so-called “Independents” desired a complete victory.

The Independents re-organised the army, forming the New Model Army, in 1645. The story of Naseby is well documented and will be noted only briefly here in this article principally about the West Riding.

The Battle of Naseby, fought in Northamptonshire on 14th June 1645, was the decisive battle between the Royalists and the New Model Army. The Parliamentarians, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, had 14,000 disciplined and well trained troops and the King could only field 9,000 men – the Royalists lost six men for every one of their opponents’.

Afterwards, the King was never again able to muster an army strong enough to oppose the Parliamentarians in a major engagement. Even so, the war dragged on until, in May 1646. King Charles eventually surrendered to the Scottish Army at Newark. The King was taken captive and handed over to the Parliamentarians.

Negotiations between the King and Parliament took place over the next three years, but eventually failed. During this time, clashes between the two armies continued.

Destruction of Thornhill Hall

In 1648, 200 Royalist troops from Pontefract marched to Thornhill Hall, the seat of Sir William Savile (at Thornhill, Dewsbury) to obtain arms and provisions to supply Pontefract Castle. Sir William had been killed in battle, but his widow Anne was still working for the Royalist cause and kept the hall fortified and provisioned.

However, a Parliamentary force of 700, under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, pursued them towards Thornhill Hall and laid siege to the Hall from across the river. The Rollson map of Thornhill, drawn in 1634, showed that the great park of Thornhill Hall then stretched as far as the River Calder in the direction of Earlsheaton and Ossett. Some of the Parliamentary troops arrived in Ossett and set up cannons at the bottom of Runtlings Lane on raised ground above the river Calder, which bombarded the Hall from across the river.

The 1775 map of Ossett and Thornhill shows that Runtlings Lane would have originally led all the way down to a small escarpment above the river, where the cannons were presumably sited. The cannons were at a distance of at least 1400 yards from the Hall, across the river Calder. That seems to be a very long way, but 17th century siege cannons had a maximum range of between 1500 and 7500 yards* depending on their size, so it was well within range of the hall. Although aiming was difficult and Civil War cannons were not therefore very effective, being fired on could break the morale of the besieged.

| *Cannon type | Maximum range (yards) – estimates vary according to source |

| Falconet | 1500 |

| Saker | 4000 |

| Culverin | 7500 |

The Royalist troops were eventually forced to surrender. During the surrender, a gunpowder explosion destroyed part of the hall, and the remainder of the building was destroyed by fire. No cause of the explosion has been determined. Whether it was the result of accidental ignition of its store of gunpowder by the defenders, or was deliberately ignited by the attackers, is unclear.

Some ruins of the house and the intact moat still remain at Thornhill Rectory Park. The images show the remains of the moat today and a 19th century drawing of the ruins.

© Christine Widdall 2019