Are You Mad?

“All the world is queer save thee and me,

and even thou art a little queer.”

Robert Owen

The charity “Mind” reports that approximately 1 in 4 people in the UK will experience a mental health problem each year. In England, 1 in 6 people report experiencing a common mental health problem (such as anxiety and depression) in any given week.

Mental illness can strike at any family from the Royals to the least wealthy…it does not respect rank, education or ability and I write without embarrassment that madness runs through my family. My interest in the treatment of mental illness was kindled when I discovered that some of my direct ancestors were committed to the Wakefield Asylum. Another of my ancestors may have suffered mental illness…those who have read my article on George Archer at Passchendaele will remember that I believe he suffered from shell-shock or PTSD as we would now call it, a nervous breakdown caused by fear, fatigue and horrific experiences. More recently, I remember the death of my greatly loved grandmother, in Storthes Hall Mental Hospital, (at Kirkburton, Huddersfield).

Am I mad myself? Well, some may think that but I could hardly comment! It’s Christmas Eve and, instead of having sherry and mince pies, I’m writing an article on insanity. But then:

Writing is a form of therapy; sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose or paint can manage to escape the madness, melancholia, the panic and fear which is inherent in the human situation.

Graham Greene

Are you mad?

I decided to take a closer look at insanity in history and at the asylums of the West Riding where my ancestors were treated.

Early beliefs about cause and treatment

The Ancient Greeks associated mental illness with physical sickness. All illness was explained in terms of the four humours, “blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm”. The balance of those things were thought to affect temperament and character, and if they became out of balance, it could precipitate a person into bodily illness or a mental state of melancholy or madness.

In the middle ages, superstitious views about spirits and demons dominated within the Christian church, and also within the doctrines of Jewish, Chinese and Islamic societies…madness might be considered to be a “punishment by God” for sins committed. So the idea of driving out demons by ritualistic exorcism became widespread in religious communities. Exorcism involved insulting the demon so much, or making the patient’s body so uncomfortable a hiding place, that the demon was driven out. Sometimes the patient died during the process, of course, but at least that meant the demon was gone.

One of the earliest known treatments for madness is depicted in a painting “The Extraction of the Stone of Madness” by Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) which shows trepanning being undertaken on a mental patient. This involved cutting a hole in the patient’s skull to allow the demons to escape. A bored nun looks on, bizarrely balancing a book on her head, whilst a priest hugs a wine jug; whether the wine was to revive and fortify himself or anaesthetise the unfortunate patient is unclear. The physician who is administering the treatment looks madder than the rest as he appears to be wearing a wine funnel on his head. I suppose that if the patient had increased pressure on the brain caused by a tumour, trepanning might have helped but on the whole it was more likely to kill. A quick visit to the tomb of St Thomas Beckett at Canterbury Cathedral might have worked better. Such visits to saintly places were reputed to have a very beneficial effect on madness.

By the 18th Century, “hydrotherapy” became popular as a treatment. Patients were repeatedly immersed in freezing water. It didn’t work too well in curing the madness, but like other treatments popular at the time e.g. powerful emetics, purgatives and blood-letting, it probably frightened or shocked the patients into more docile behaviour. This might have given the impression of temporary improvement, naturally leading to a requirement for further doses to be administered…and it became a self perpetuating nightmare for the patient

Rotational therapy, said to have been invented by Charles Darwin’s grandfather, involved spinning the patients until they were dizzy and vomited. The idea was that spinning would calm the patient. Naturally, that didn’t work long-term either, though the patient might be calm for a while after feeling so ill.

We’ll return to treatments in a while. They didn’t really become much kinder, but they did become different. For now, let’s consider how you can tell if somebody is mad.

How do you tell if somebody is mad?

The Victorians believed that you could tell if somebody was mad by looking at their face. This set of images, taken from the book ‘A Manual of Psychological Medicine’ by Bucknill and Tuke (1858), depicts men and women committed to the Devon County Lunatic Asylum. How many of them look mad to you?

Here are some more photographs from the 1860s, depicting insane people, with a diagnosis of their ailment written at the bottom of each one. (Click on each image in turn to see more clearly).

Faces of insanity images above © Wellcome Collection [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The 18th Century Madhouse, 19th/20th Century Lunatic Asylum and 21st Century Mental Hospital

Until mental asylums were conceived, most mentally ill individuals were cared for within the family. This would have been relatively easy for rich families who could engage a nurse to look after the patient. The mad relative would be hidden from view, like Mr. Rochester’s mad wife Bertha, in Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre”.

But for poor families, caring for someone with mental illness, or any acquired or congenital condition affecting the brain, would be very difficult. Many families worked long hours to earn enough to keep themselves and would not have the time to devote themselves to the 24/7 care of a needy relative. Putting the individual into the workhouse to be “out of sight and out of mind” became a necessity for many, as the publicly funded mental hospital did not yet exist. Some mentally ill paupers even lived on the streets as beggars (sounds familiar?).

The earliest asylum for the insane was the Bethlem Royal Hospital in London (fondly called Bedlam), where everything was self-contained. Bedlam was founded in 1247 as a centre “for the collection of alms to support the Crusader Church and to link England to the Holy Land”. By the 15th century, it had become a place for the care and treatment of the insane. In 1632, Bethlem Royal Hospital had…

below stairs a parlour, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in.

Credit: Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Originally just outside the city walls, Bedlam moved to Moorfields in the 17th century, then to Southwark in the 19th century. It is now at West Wickham.

For the Georgians and Victorians, exhibitions of curiosities regularly drew fascinated sightseers and members of the public could pay to enter Bedlam to observe the patients, as a way to raise money for the hospital.

The Asylum

The asylums of the late 17th century were built with the intention of caring for the mentally insane in environments that were moral and safe and clean, providing a place where rest and care might restore the patient to sanity. They were mostly small privately run affairs, grand houses in secluded locations, where the wealthy could have their “insane or disturbed” relatives taken care of in comfort, safely and seclusion. Sometimes, mentally ill paupers could be housed in such private asylums, but only if paid for out of the coffers of the local parish. Well, that was the theory, anyway. Setting up a madhouse was not difficult:

There was a need for places which could provide accommodation for the mad for a fee, and thus grew an interesting outlet for the entrepreneur; open a mad house (for this is what they were called). No training required, no regulation, charge what you want, take in who you want. Money to be made! Roll up, roll up. What could go wrong? People did this and some made a great deal of money from it. For much of the eighteenth century there was no state regulation or responsibility for the daily happenings or day-to-day management of private asylums. Consequently, numerous private madhouses became subject to public scandals, accused of horrific abuses, malpractices, and patient mistreatment.

Malcolm Byard, Yorkshire historian

Some mad houses were appalling places. Others, usually those which charged large fees and thus attracted the richer client, were more acceptable. There was a problem, however, in that some people were placed in mad houses who were not actually mad, they were just inconvenient…of particular public concern was the issue of wrongful confinement. Notable cases included a wife imprisoned by her husband for lacking passion and acting “indifferently” within the bedroom and young girls locked up to end love affairs of which their parents did not approve. Women in particular were susceptible to wrongful confinement by husbands or fathers, including…

…young women with money at their disposal who refused to cooperate with their families, generally on the matter of marriage.

Max Byrd

Admittance to the asylum was usually against the will of the patients and easy enough to achieve, but once inside, it was difficult for patients to obtain their release and many sane individuals remained in the asylum for the rest of their lives. I wonder how long it took a wrongly confined sane individual, with no hope of release, to actually become insane? When thought to be cured, the lucky few were released back into the community, but the stigma of madness remained with them and might prevent them from marrying or gaining employment, leading to recurring bouts of despair and madness, return to the asylum, the workhouse, or sometimes even suicide.

A 1774 Act of Parliament had required all asylums to be registered and inspected…this was a step forward but there was no attempt at introducing therapy in most asylums…containment and restraint were the orders of the day. Just over twenty years after this law was passed, tea and coffee merchant William Tuke led the development of a new type of institution in Yorkshire. In 1792, with the help of fellow Quakers, he founded the York Retreat, where around 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house. The treatment consisted of rest, talking therapy, and light manual work. But this was not the norm and its model was not to be followed for the vast majority of mental patients.

County Asylums Act 1808

The very varied quality of the private asylums and a need for the provision of care for the poor who were mentally ill, led to the passing of the County Asylums Act 1808. This authorised the establishment of publicly funded county asylums. From the early 1820s there was a surge in building of such asylums which became the places where “pauper lunatics, insane persons and dangerous idiots” would be incarcerated and treated. At last, mentally ill people, who were unable to pay, could be admitted to a place of safety and care at public expense.

Reasons for admittance to the Asylum included dementia, melancholia, mania and feebleness of mind…many times no diagnosis was given…just what was believed to be the cause, so these included domestic affliction, injury to the head, epilepsy, religious anxiety, intemperance, masturbation, puerperal (circumstances arising from childbirth), venereal disease, studying astrology, pecuniary misfortune and disappointment in love!

As the asylums multiplied, the number of people certified as “insane” soared. More and more people arrived, and fewer and fewer ever left.

The West Riding Asylums

The West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum, the first in West Yorkshire, was opened at Stanley Royd, just outside Wakefield, in 1818. It became one of the most important centres of research into madness in the world. Perhaps I should say that I am relieved that it was here that my 2x and 3x great-grandfathers were treated and that their confinements were as late as 1884 and 1895 respectively, when the very worst of asylum brutality had passed.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Stanley Royd was a pioneer in the emerging discipline of biological psychiatry. It had an in-house laboratory which researched into “cerebral localisation”, searching for the exact locations for the control of the various functions of mind and body. It also housed a large collection of pathological specimens for teaching purposes. Its doctors studied the problem of insanity in new scientific ways under its Director, Dr. Crichton Browne, and a “liberal and enlightened Board of Governors.” Browne became something of a celebrity and wrote articles for the local press and for the “Gentleman’s Magazine”. He lectured at the Leeds School of Medicine and founded and edited the annual West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports.

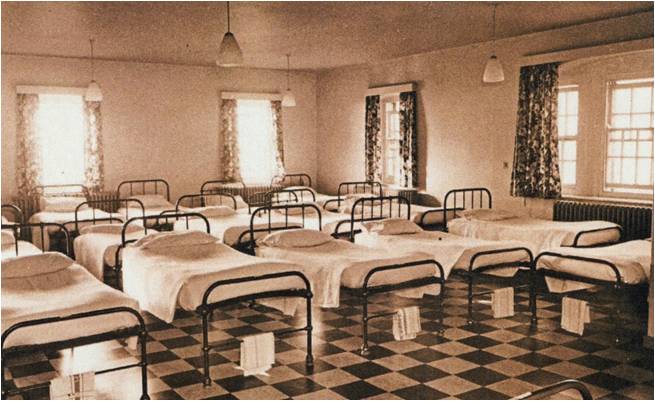

Men and women slept in clean dormitories. During the day, patients who were able were expected to help out in the laundry or outdoors. The images below are from Stanley Royd Asylum, c1900.

Most staff members seemed to be expected to be able to play a musical instrument. Entertainment of the patients was seen to be very important. Plays and concerts were popular and, when moving pictures became available, a regular film show would be given.

In spite of all of this innovation, the aetiology of insanity was still mostly unknown…and more patients were being admitted than discharged. It soon became clear that the Wakefield (Stanley Royd) Asylum could not keep up with demand and further asylums were built in the West Riding at Middlewood, Menston (High Royds) and at Storthes Hall.

It was at Storthes Hall that my grandmother was treated on a number of occasions and where she died in 1972…more about that below.

Treatments 19th-21st Centuries

As ideas of invasion of the body by demons became outdated, and with the emerging of the medical sciences, most doctors began to accept that there was a medical cause for many forms of mental illness. But, since the causes of such conditions was still not well understood, the treatments for psychiatric problems were very limited and not very effective.

By the early 19th century, possibly well meaning, if sometimes misguided, doctors were attempting to treat mental illness and experimented on patients in ways that we would now describe as torture.

Water treatment was still popular. Mental patients might be put in cages and lowered into deep cold water. Once the bubbles stopped rising, the patient was pulled out and revived in the hope that the shock of the treatment would restore the balance of the patient’s senses…or the patient was restrained in a chair to prevent movement, then icy water was poured on the head and hot water on the feet, to reduce blood flow to the brain.

Patients might be manacled to the wall or kept in padded cells. Leather masks that covered the face and fastened by leather straps in the back were sometimes used. Mittens were used to prevent the patient from scratching and strait jackets held their arms against their chest. Spinning patients until they vomited was still a way thought to “shock people back to sanity”.

Asylum attendants had little or no training and could treat the patients cruelly, even brutally. Some doctors thought that madness that could only be proven in post-mortem examination – so why was there a need to keep them alive anyway? The insane were more useful dead weren’t they? Unfortunately, post-mortem dissection of the brain did not identify the cause of madness in most cases, a notable exception being in “general paralysis of the insane” caused by syphilis.

As the 19th century wore on, some of the more barbaric treatments fell from favour and treatments became more palliative. Hygiene and occupational therapy became central to care. Drug therapy included opium, antimony salt, amyl nitrate and par-aldehyde. The discharge rates were now 50% but who knows how many cures were simply achieved because the patient had had time to get over the disappointment in love or pecuniary embarrassment that had brought them low, and being incarcerated had not allowed for the studying of astrology. At any rate, many who were truly mentally ill found themselves back in the asylum before very long and many more died there having lost all hope of release.

![Bjoertvedt [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/kirkleescousins.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/640px-Lobotomy_drill_norway_IMG_0982.jpg?resize=640%2C397)

© Bjoertvedt via Wikimedia Commons

In the 20th century, leucotomy/lobotomy of the brain became alternative treatments for serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia and severe depression. In 1935, Portuguese neurologist Antonio Egas Moniz first performed a brain operation called “leucotomy”. This involved drilling holes in his patient’s skull to access the brain and severing connections in the brain’s pre-frontal cortex. In 1936, Walter Freeman and another neurosurgeon performed the first prefrontal leucotomy (lobotomy) in America. The belief was that cutting nerves within the brain would eliminate excessive emotion and calm the patient. Tens of thousands of lobotomies were performed as treatment for schizophrenia, severe depression and bipolar disorder. It was a treatment of desperation and many patients were irreparably damaged by the procedure, experiencing negative effects on their personality, initiative, empathy and ability to function on their own (remember the film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest?) and 5% of patients died from it. A study of several hundred patients post-operatively found that around a third had benefited, a third were unaffected and a third were worse off afterwards. Lobotomy is rarely performed today.

Treatment with the drug Metrazol began around this time as did Insulin Coma Treatment and ECT (Electroconvulsive Therapy). ECT is a treatment that involves sending an electric current through the brain to trigger an epileptic fit to treat some mental health problems, including severe depression, manic or psychotic episodes and catatonia. The electric stimulus changes the blood flow in the brain and may change brain chemistry. It was used extensively in the mid 20th century and is still in use today. Current treatments also include Talking Treatments, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and Drug Therapies.

Family Case Notes

Robert Archer (c1815-1884)

Robert Archer’s death certificate shows that he died on 23rd August 1884 in the Lunatic Asylum at Stanley Royd, Wakefield. A post mortem showed that he had heart disease. His age was given as 70. On 12th July 2000, my distant cousin and genealogist Elizabeth consulted the records of Stanley Royd Lunatic Asylum and was able to access Robert’s records. Below is a summary.

Patient no 9151, Robert ARCHER admitted June 27 1884. Age 70. Married. Mechanic of Soothill, Dewsbury. Height 5’5″ Weight 122 lbs. Bodily condition: Fairly well nourished. Complexion: Earthy.

The patient’s notes included the following summary from his GP:

The man seems very depressed and slow in giving answers. He frequently wanders about in an aimless way and when he calls here, I have difficulty getting much information out of him. His wife tells me he sleeps badly, eats voraciously, is very depressed and speaks about doing away with himself. He said yesterday he would jump head first into the wine tub and also that all things have a very curious look.

His inpatient notes reported that the illness had been coming on for the last 3-4 years. The illness had begun with loss of memory, strangeness of manner and irritability. He would go out for a stroll and forget where he had been. He had done no work since the attacks began and had been very quarrelsome with his family. He had become suicidal and dangerous to others. In the last few years he had occasionally threatened to fill his mouth with gunpowder and set fire to it. In July, Robert was described as less depressed. On August 12th, he had oedema of feet and was in a generally feeble state. He was given a stimulant of 3 measures of whisky daily. He died at Stanley Royd on August 23rd 1884, at 8.40 am.

Smith Archer (Robert’s son) (1845-1901)

I have not yet accessed Smith’s records (note to self to do this).

From: Stanley Royd Asylum Index 1890-1895: Admission and Discharge Records show that Smith Archer was admitted to Stanley Royd and spent four months as an in-patient in 1895. The record does not show his illness, but does show that he recovered.

Admitted April 22nd 1895, aged 50 – Discharged August 20th 1895.

Edward Archer (Smith’s son) (1873-1961)

Edward did not enter the asylum at any time, but, from his mid 80s, he exhibited unusually distant moods and strange behaviour. He became deaf but heard voices that nobody else could. He also used to sometimes disappear from home for days on end and would be found roaming the streets of Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire (55 miles away)…always Scunthorpe…often to be returned home by the police…he would say that he had gone there looking for a man who owed him money. Edward was very afraid of being committed to the workhouse…even though it didn’t exist anymore…did he remember family members who had been committed there? He was cared for at home by my grandparents, George and Mary Archer until he was taken into the local general hospital with pneumonia, from which he died in 1961, aged 88.

George Archer (Edward’s Son) (1895-1972)

I strongly suspect that my grandfather suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after WW1, then known as Shell Shock. See “George Archer at Passchendaele”.

To develop PTSD you must have experienced trauma, as in WW1, but not everyone who experienced trauma became a sufferer of PTSD (Shell Shock). The ones who did may have been predisposed to developing the illness, because of a family history of susceptibility. We may have identified that there was such susceptibility in the histories of George’s own father, grandfather and great-grandfather.

Lilian Maud Sheard (1890-1972)

Around 1897, the West Riding Asylums Committee decided to build their fourth pauper lunatic asylum and purchased Storthes Hall, at Kirkburton near Huddersfield, together with a large part of the estate, from Thomas Norton, in 1898. Ward blocks were built over the next years and Storthes Hall Asylum was opened in 1904. It became the Storthes Hall Mental Hospital in 1929, and finally the Storthes Hall Hospital from 1949.

My greatly loved grandmother, Lilian Maud Sheard, was admitted to Storthes Hall Hospital on several occasions in the 1960’s/early 1970s. She was treated with several cycles of ECT therapy each time and was an inpatient for several weeks. When returned home she was quiet and disorientated, but she gradually returned to her normal kind and gentle self…though she suffered some permanent memory loss, especially for people’s names. She would cycle round the family names until she landed on the right one. Between bouts of severe depression, she was her perfectly “normal” cheerful self.

Worryingly, Storthes Hall Hospital was one of several hospitals which were investigated in 1967 as a result of Barbara Robb’s book “Sans Everything”. Robb was a Psychotherapist and was appalled at the behaviour of staff that she witnessed towards mental patients in a number of institutions. This she exposed in her book. At Storthes Hall…

Accusations covered a thirty-two-week period of serious violent assaults with fists or weapons…committed by four named male nurses. It was also alleged that it was a brutal, bestial, beastly place…it was a hell-hole.

After investigation, the report found none of the allegations against any named or unnamed member of the hospital staff to have been proved. Of course, that does not mean that they didn’t happen.

Storthes Hall remained a place that my grandmother dreaded and to where she was forcibly taken. Unfortunately her episodes of severely depressive illness always returned and she was admitted again to Storthes Hall late in 1971. I visited her there at Christmas and took her a little brooch that I had bought with amethyst coloured stones…but she didn’t really respond and she died soon afterwards, still an in-patient, in January 1972. She was 81 and had outlived her husband, who was 10 years her junior, by three years.

Time for sherry and mince pie…Merry Christmas.

Christine Widdall 24th Dec 2018

I am indebted to Malcolm Byard, Yorkshire Historian, for sharing his research on madness with me and have used some of that research in my article.