Civil War – Events in 1643

Huddersfield January 1643

Around Huddersfield, there was a great deal of tension, as the citizens, including tradesmen and clothiers, were mostly for the Parliament, but the gentry were Royalists.

A handful of skirmishes took place around Huddersfield, including on January 4th 1643 when about 500 Parliamentarians ventured into Emley and took Michael Green, the Constable, prisoner, only to release him two days later.

Seventeen days later, 1,000 Parliamentarian soldiers raided Kirkby Grange at Emley where they took horses and money.

Huddersfield Examiner

Battle of Leeds 23rd January 1643

The inhabitants of the clothing districts began volunteering more quickly than Thomas Fairfax could train or arm them. By early January, he had managed to recruit an army even larger than his father’s, comprising 600 musketeers and 3000 men at arms, including about 1000 untrained irregulars (known as clubmen).

Thomas Fairfax soon took his opportunity to attack the Royalists and Leeds was his first target, then a relatively small wool town, but strategically important as the Royalists were garrisoned there. Taking with him six troops of horse, dragoons, musketeers and footsoldiers, Thomas Fairfax divided his forces and attacked Leeds from both sides of the River Aire, at three separate points, on 23rd January 1643.

The Royalists resisted fiercely for two hours, but were finally overwhelmed. Cut off from escape by the bridge, they were driven back to their headquarters near the parish church. They eventually attempted to escape by swimming across the River Aire, and many of them succeeded in doing so, though some inevitably were drowned. Fairfax and his Parliamentarians quickly occupied Leeds, taking 500 prisoners, two cannons and a store of weapons and ammunition. In Sir Thomas Fairfax’s words:

Summoning the country (calling in volunteers) we made a body of about 1200 or 1300 men with which we marched to Leeds and drew up within half cannon shot of their works…and sent in a trumpet with a summons to deliver up the town to me for the use of King and parliament.

…they returned this answer…that they would defend the town as best they could…the business was hotly disputed for almost 2 hours…the enemy were beaten from their barricades…were forced open to the streets, where horse and foot resolutely entering, the soldiers cast down their arms…the governor and chief officers swam the river and escaped…in all there were about 40 or 50 slain and a good store of ammunition taken which we had much want of.

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

Reinforcement

On 2 February 1643, Lord Fairfax decided to appeal to the entire county of Yorkshire for support, sending a “declaration to muster” to all mayors, bailiffs, aldermen, magistrates and ministers, to be published and proclaimed in all the county’s churches and markets, saying:

All men of able bodies and well affected to the protestant religion are required with the best weapons and furniture for the warr that they have to assemble, come in and assist mee and the army under my Command in expelling and driving away out of this County of the Earle of Newcastle his Army of Papists and common enemies of the peace, each man bringing with him necessarie victualls for four dayes ýonely

In: THE EXTENT OF SUPPORT FOR PARLIAMENT IN YORKSHIRE DURING THE EARLY STAGES OF THE FIRST CIVIL WAR; Andrew James Hopper; University of York.

Fairfax also wrote to the Constables of the various towns. His letter to the Constable of Mirfield demanded:

…all that be of able bodyes from the age of 16 to 60 to repair to Almondbury on Saturday, with all weapons they can procure and provisions for five days, to assist in driving out the Papist army…fail not at your peril.

The History of Mirfield; Bernard G Kaye

The people of Holmfirth “sent forth a hundred musketeers for the Parliament’s service”, but paid the price when their houses were later burned down by the Royalists.

Belasyse attacks Bradford, 25th March 1643

On 25th March 1643, Belasyse and Porter once again attacked the Parliamentarian garrison at Bradford. This time the attack almost succeeded; after fighting off several fierce Royalist assaults, the Parliamentarians were running low on ammunition. In desperation, their commander, Colonel Lambert, attempted to break out of the town. The breakout took the Royalists by surprise and, unexpectedly, the Parliamentarians destroyed Porter’s cavalry. Lambert quickly reoccupied Bradford and resumed its defence while John Belasyse, deprived of most of his cavalry, withdrew and Porter returned to Newark in disgrace.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man? In the case of Bradford it should be Cometh the hour, cometh the men, as the ill-armed, and vastly outnumbered, citizens of the town had, beyond all reason, not only held the town, but sent their enemies scurrying back to Leeds in disorder.

David Cooke, The Civil War in Yorkshire.

Seacroft Moor (Whinmoor) 30th March 1643

Towards the end of March 1643, Lord Ferdinando Fairfax decided to withdraw from Selby and consolidate his Parliamentary forces by marching his 1500 men from Selby to Leeds.

To cover his father’s withdrawal from Selby, Sir Thomas Fairfax made an attack on the town of Tadcaster on 30th March with 1000 footsoldiers and 200 horse. The Tadcaster Royalists fled towards York at Fairfax’s approach, and Fairfax took the opportunity to enter the town and to destroy Tadcaster’s defences, though he failed to destroy the bridge.

Fairfax and his troops now set off to join his father in Leeds. It was warm weather and the troops had marched from Selby to Tadcaster, entered the town and destroyed the town’s defences and they were very tired and thirsty. As they crossed Bramham Moor safely and reached some enclosed fields at Kiddal or Potterton (hamlets near Barwick-in-Elment) they sought refreshment at local houses. Afterwards, they made slow and disorderly progress towards Seacroft, on the outskirts of Leeds.

The Earl of Newcastle had reacted quickly and sent Lieutenant-General George Goring with twenty troops of horse and dragoons to the area, who were following behind the Parliamentarians. As Fairfax’s troops reached Seacroft Moor (Whinmoor), Goring attacked them. The Parliamentarians were heavily outnumbered and outflanked by the Royalist cavalry (the Parliamentarians had mainly volunteer infantry, including musketeers, very few pikemen and just 3 troops of horse whereas the Royalists had 20 troops of horse).

Thomas Fairfax’s volunteer infantry broke and fled almost immediately…200 Parliamentarians were killed and 800 were taken prisoner…most of his footsoldiers and his troops of horse. Fairfax managed to rally a few officers to make a fighting withdrawal to the safety of Leeds, arriving two hours after his father, whose army had arrived safely. The defeat at Seacroft Moor was a serious early blow to the Yorkshire Parliamentarians and Sir Thomas Fairfax wrote afterwards:

…it troubled me much, the enemy being close upon us and a great plain to go over, so marching the foot in 2 divisions and the horse in the rear, the enemy followed about 2 musket shot from us…but yet made no attempt on us and thus we got well over this open country.

But having again gotten to some little enclosures beyond which was another moor called Sea Croft Moor (much less than the first) here our men thinking themselves more secure were more careless in keeping order and while their officers were getting them out of the houses where they sought for Drink, it being an extream hot Day, the Enemy got another Way as soon as we into the Moore; and when we had almost pass’d this Plain also, they seeing Us in some Disorder, charged Us both in Flank and Rear.

The Countrymen presently cast down their Arms and fled; the Foot soon after, which for want of Pikes was not able to withstand their Horse: Some were Slain, many were taken Prisoners; Few of Our Horse stood the Charge. Some Officers with me, made Our Retreat with much Difficulty; in which Sir Henry Fowlis had a slight Hurt; my Cornet was taken Prisoner. We got well to Leeds, about an Hour after my Father and the Men with him got safe thither.

This was one of the greatest Losses we ever receiv’d. Yet was it a Providence, it was a part and not the whole Forces which receiv’d this Loss; it being the Enemy’s Intention to have fought us that Day with their whole Army, which was at least Ten Thousand Men, had not Our Attempt upon Tadcaster put a Stand to them; and so concluded that Day with this Storm, which fell on me only.

We being at Leeds, it was thought fit to possess some other Place; wherefore I was sent to Bradford with seven or eight hundred Foot, and three Troops of Horse. These two Towns were all the Garrisons we had…

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

Newcastle believed he could now use his army of 10,000 men to completely finish off the Fairfaxes. But the Fairfaxes were not yet finished. Many of the prisoners taken at Seacroft Moor were local conscripts with wives and families. In order to attempt their release, Lord Fairfax decided on a raid on Royalist-held Wakefield.

Wakefield 20th May 1643

The Wakefield garrison was expected to be 800 strong but in fact they outnumbered the Parliamentarians three to one. Thomas Fairfax travelled via Bradford and Halifax to Howley Hall (near Batley), setting out at two in the morning on 21st May 1643. They marched from Howley Hall via Ardsley, Lawns and Outwood, towards Stanley. By now, Fairfax had between 1100 and 1500 horse and foot soldiers, which seemed to be more than enough to take a garrison of 800 in a surprise dawn attack.

However, the Royalists were ready and waiting with musketeers lined up on the outskirts of Wakefield. After two hours of fierce fighting, Fairfax led a cavalry charge through a gap in the defences and into the streets of Wakefield. Pushing too far ahead, Fairfax found himself almost alone in the market-place and surrounded by Royalist troops but he escaped by jumping his horse over a barricade to rejoin his own troops.

By 9 am it was all over and Wakefield was in the hands of the Parliamentarians. Fairfax was astonished to find that the Wakefield garrison had consisted of 3,000 men, comprising infantry and seven troops of horse as well as a huge store of ammunition, not just the 800 men that they had expected. George Goring, Royalist leader, was taken prisoner and confined in the Tower of London.

The victory gave Fairfax 3,000 captured arms and 1400 prisoners to exchange for those taken at Seacroft. In Fairfax’s words:

So upon Whitsunday we came before the town, but they had notice of our coming and had …set about 500 musketeers to line the hedges about the town…after two hours…the foot forced open a barricade where I entered with my own troop….we charged through and routed…after a hot encounter, some were slaine…my men brought up a piece of ordnance and planted it in the churchyard against the body (of men) that stood in the market place who presently rendered themselves.

All our men being got into the town, the streets were cleared. Many prisoners taken…we saw our mistake now finding 3000 men in the town, not expecting half that number. We brought away 1400 prisoners …(and) we exchanged our men that were prisoners with these.

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

Adwalton (Atherton) Moor, 30th June 1643

The Earl of Newcastle, meanwhile, had resumed operations against the clothing towns of the West Riding, this time with success. The Royalist Army marched into the parish of Birstall (between Leeds and Bradford) and there followed the battle of Adwalton Moor, five miles south-west of Bradford. Fairfax deployed 10 troops of horse and 2,500 foot from the West Riding Cloth towns. They were strengthened by three companies of horse recently arrived from Lancashire. However, they were little more than 3,000 men against 12,000. The Parliamentarians put up strong opposition but were too weak for Newcastle’s larger forces and they were heavily defeated.

Sir Thomas Fairfax wrote:

…Our Men lost Ground, which the Enemy seeing, pursued this advantage, by bringing on fresh Troops; Ours being herewith discouraged, began to fly, and were soon routed. The Horse also Charged us again, We not knowing what was done in the Left Wing: Our Men maintained their Ground, till a Command came for us to Retreat, having scarce any way now to do it, the Enemy being almost round about us, and Our way to Bradford cut off.

But there was a Lane in the Field we were in, which led to Hallifax, which as a happy Providence, brought us off, without any great Loss, save of Captain Talbot, and twelve more that were slain in this last Encounter. Of those who fled, there were about sixty kill’d, and three hundred taken Prisoners.

After this ill Success, we had small hopes of better, wanting all things necessary in Bradford for defence of the Town, and no expectation of help from any Place.

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

Sir Thomas Fairfax managed to reach the relative safety of Halifax, with what remained of his troops. His father, Ferdinando, eventually reached the relative safety of Leeds, then on to Bradford.

The Hothams, left in charge of the town of Hull for the Parliament, had recently defected to the Royalists, leaving the Fairfaxes with no East Yorkshire stronghold and, after their major defeat at Adwalton Moor, the Parliamentarians’ only hope in Yorkshire was to defend Bradford, their last major stronghold in the area.

2nd Siege of Bradford 1st-3rd July 1643

The Earl of Newcastle set up his headquarters at Bolling Hall in readiness to besiege Bradford. Tom Fairfax afterwards wrote:

The Earl of Newcastle presently Besieg’d the Town; but before he had surrounded it, I got in with those Men I brought from Hallifax. I found my Father much troubled, having neither a place of Strength to defend our selves in, nor a Garison in Yorkshire to Retreat to; for the Governour of Hull had declar’d if we were forced to Retreat thither, he would shut the Gates on us.

Whilst he was musing on these sad thoughts, a Messenger was sent unto him from Hull, to let him know the Townsmen had secured the Governour; that they were sensible of the danger he was in, and if he had any occasion to make use of that Place, he should be very readily and gladly receiv’d there. Which News was joyfully receiv’d, and acknowledged as a great Mercy of God, yet it was not made use of till a further necessity compell’d.

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

Lord Fairfax decided that his force must attempt to break out of Bradford at dawn. The footsoldiers went out through some narrow lanes and Ferdinando Fairfax himself was accompanied by his horse soldiers and they set off to attempt to secure Leeds. Sir Thomas Fairfax covered his father’s escape and remained in Bradford until early on the 3rd July.

The Earl of Newcastle had brought down his cannon and made repeated assaults in the town on the 1st July. The next day, a Sunday, the Earl of Newcastle sent in a messenger offering a cease fire, which Thomas Fairfax agreed to accept, to prevent the deaths of the citizens. Fairfax twice sent out two Captains to negotiate over the next few hours, but Newcastle was using the time to his advantage and moving his artillery to a better position, from where they could fire directly into the heart of the town.

The townspeople of Bradford had converted the church into a fortress, hanging wool sacks on the side of the now famous church steeple, but the defenders only had 25 barrels of gunpowder. The citizens must have feared the worst that night, as the Royalists increased their bombardment of the town.

Imagine every countenance overspread with sorrow; every house overwhelmed with grief; husbands lamenting over their families; women wringing their hands in despair; children shrieking, crying and clinging to their parents; death in all its dreadful forms and frightful aspects, stalking in every street and every corner; in short horror! despair!

Joseph Lister, citizen of Bradford, eyewitness.

After fighting off two major assaults, Bradford’s defenders were down to their last barrel of powder and no match. Thomas Fairfax was unable to defend the town and now we can read his own words…

Bradford July 1643

My father, having ordered me to stay (in Bradford) with 800 foot and 60 horse…he intended that night for Leeds to secure it.

Newcastle having spent 3 or 4 days in laying in his quarters about the town (Bradford) they brought down their cannon within half musket shot…(and) shot furiously upon us.

Our little store was not above 25 or 30 barrels of powder at the beginning of the siege…we heard a great shooting of cannon and muskets. All ran presently to the works which the enemy was storming. Here for ¾ hour was very hot service but at length they retreated. They made a second attempt but were also beaten off.

After this we had not above one barrel of powder and no match…so (we) resolved to draw off …before it was day…and to retreat to Leeds…. The foot was sent out through some narrow lanes…myself with some other officers went with the horse by an opener way.

I must not forget to mention my wife who ran as great hazards with us in this retreat… before I had gone 40 paces (the day beginning to break) I saw them upon the hill above us being about 300 horse. I with some 12 more charged them…the rest of our horse being close behind, the enemy fell on them …taking most of them prisoners; among them my wife (the soldier behind whom she was riding being taken); I saw this disaster but could give no relief…I stayed till I saw there was no more in my power to do but to be made a prisoner with them.

Short memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax written by himself

On arriving at Leeds, Thomas Fairfax found some 80 infantrymen who had also escaped from Bradford and a small garrison left behind by Lord Fairfax.

The next morning, the Royalists entered Bradford and pillaged it, emptying sacks of grain into the streets and filling the empty sacks with all valuables they could find, while the Earl of Newcastle turned a blind eye. Without protection from Fairfax’s force the townspeople were expecting to be put to death…

But oh! what a night and morning was that in which Bradford was taken! what weeping, and wringing of hands! none expecting to live any longer than till the enemies came into the town, the Earl of Newcastle having charged his men to kill all, man, woman, and child, in the town, and to give them all Bradford quarter (i.e. no quarter)…however, God so ordered it, that before the town was taken, the Earl gave a different order, that quarter should be given to all the townsmen.

Joseph Lister, citizen of Bradford, eyewitness.

The town was left under the control of a small garrison of Royalists until 1644. Some days after Bradford was taken, Newcastle sent Tom Fairfax’s wife back to Hull in his own coach, with some cavalry to guard her, as a gesture of goodwill.

The Parliamentarians’ defeat at Adwalton Moor and loss of Bradford, allowed the Royalists to take full control of West Yorkshire and Lord Ferdinando Fairfax now ordered that Leeds should also be evacuated. The Hothams of Hull, father and son, had recently been taken prisoner by the citizens of the town and executed as turncoats…so Hull was now available again to the Fairfaxes and that needed to be held at all costs, as it guarded the sea route into East Yorkshire.

Thomas Fairfax, with his remaining soldiers, abandoned Leeds and followed his father, retreating towards Hull via Selby and Barton-on-Humber. On the way, he surprised Royalists at Selby and a cavalry engagement took place, where Fairfax was shot in the left wrist. In spite of his serious injury and much blood loss, Fairfax continued to lead his troops, which were engaged in skirmishes with Royalist troops most of the way. They reached the relative safety of Hull on 4th July 1643.

Due in part to the sacking of the town and subsequent starvation, an epidemic of illness affected Bradford after the second siege, which set the town back considerably. As a result of this, Bradford lost its prominence in the area, with Leeds becoming the leader in trading.

Halifax in Royalist Hands

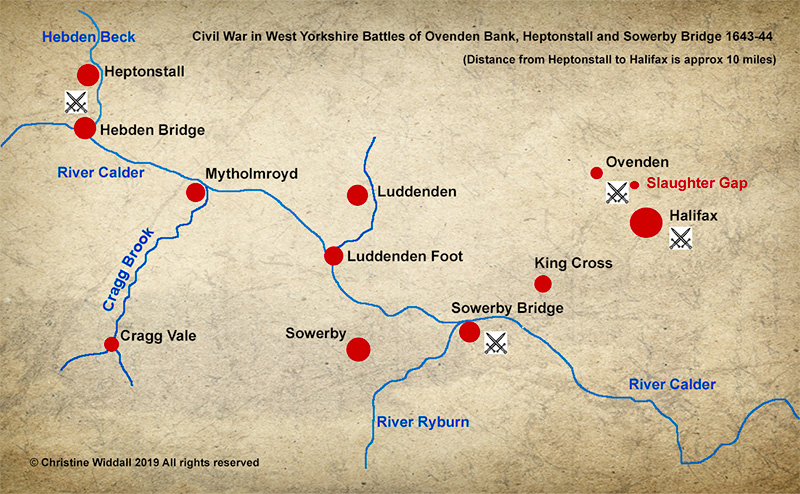

On or about the 4th July, Sir Francis Mackworth, with a force of Royalist soldiers, was commanded to occupy Halifax. With banners flying and drums beating, they marched towards the town unopposed until, approaching Halifax from the north, they were engaged by a small determined force of Parliamentarian defenders at a place which became known as the Bloody Field of Ovenden Bank. There, the Royalists routed their opponents. Royalist troops now occupied Halifax and surrounding townships, setting up garrisons at Sowerby Bridge and King Cross to the south-west of the town.

Many of the defeated Parliamentary troops fled over Blackstone Edge into Lancashire, where they would await further orders. Many of the townspeople, supporters of Parliament, loaded what possessions and provisions they could carry onto horses and carts, gathered their children, and also made a difficult journey over the moors into Lancashire, which was still in Parliament’s hands. Some never returned and succumbed to illness and death on the journey or soon afterwards.

By the 7th July, Royalist Cavalry under Mackworth, began to ride out from King Cross and Sowerby Bridge and attack Parliament troops from Lancashire who were defending the moorland passes. However, the slippery wet peat was treacherous for the cavalry horses and they became bogged down. The Royalists retreated and returned to barracks, believing that:

…they will hardly have passage that way, because it is naturally so strong that 500 men can keep one thousand, neither is it fit for carriages or ordnance.

The Halifax Cavaliers and Heptonstall Roundheads; David Shires.

The Royalist soldiers returned to garrison duties and to pilfering and plundering the estates of their enemies. Their foraging trips went as far as Honley, Marsden and Saddleworth. In August, the Earl of Newcastle marched back into Yorkshire with 12,000 foot and 7000 horse and “one thousand bloody women” (camp followers). Newcastle now turned his attention to the south of Yorkshire, to Sheffield.

Sheffield Castle

At the beginning of the war, the town and castle at Sheffield had been seized for the Parliamentarians…but was now to be quickly taken by the Earl of Newcastle, who appointed Sir William Savile as Governor. Margaret Cavendish, Newcastle’s wife, later wrote…

…he (Newcastle) marched with his army to Sheffield, another market-town of large extent, in which there was an ancient castle; which when the enemies forces that kept the town came to hear of, being terrified with the fame of my Lord’s hitherto victorious army, they fled away from thence into Derbyshire, and left both town and castle (without any blow) to my Lord’s mercy; and though the people in the town were most of them rebelliously affected, yet my Lord so prudently ordered the business, that within a short time he reduced most of them to their allegiance by love, and the rest by fear, and recruited his army daily;

He put a garrison of soldiers into the castle, and fortified it in all respects, and constituted a gentleman of quality, [Sir William Savile knight and baronet] governor both of the castle, town and country; and finding near that place some ironworks, he gave present order for the casting of iron cannon for his garrisons, and for the making of other instruments and engines of war.

The Life of William Duke of Newcastle; Margaret Cavendish

Events in East Yorkshire – The Second Siege of Hull

Early in September 1643, Newcastle’s troops had also occupied the towns and villages around Hull and begun building earthworks for his artillery, in preparation to besiege Hull, but the Royalist cannons were too far from the town. The Parliamentarians opened the sluice gates of the River Humber and flooded the Royalist earthworks, as they had done before, in 1642. The Parliamentarians also still controlled the seas, which enabled them to ship provisions and armaments into Hull.

By October, Lord Fairfax was also able to ferry in re-inforcemenets across the Humber, from “the Eastern Association Army” which was under the command of Oliver Cromwell. They now went on the offensive and, as Newcastle’s forces fled, Fairfax turned their own cannon on them and, on the 12th October, the siege was over. After the siege of Hull failed, the Parliamentarians under Fairfax and Cromwell went on the offensive in Lincolnshire.

Heptonstall and Hebden Bridge

News that the main Royalist force were engaged in Lincolnshire was carried to the Yorkshire troops who had fled to Lancashire after the fall of Bradford and Halifax. They now needed a commander to lead them back into West Yorkshire to attempt to retake the towns that they had lost, specifically Halifax.

The man appointed to lead them was a Manchester officer named Colonel Robert Bradshaw. He set about mustering the Yorkshire men who were now unoccupied in Lancashire, by sending out notices of intent to those churches that were used as meeting places for Parliament’s supporters. A volunteer force was put together, at Rochdale, of mostly men from Yorkshire, who knew the Halifax area and were prepared to cross the Pennines with Bradshaw to mount an attack.

On the 19th October, Bradshaw and his men marched out of Rochdale and headed east into Yorkshire. They made for the village of Heptonstall, which lies at the top of a steep hill, ten miles from Halifax, where they set up camp. Bradshaw’s “army” comprised one troop of horse (about 60 men), 280 musketeers and about 500 clubmen, the latter carrying whatever weapons came to hand, including swords, clubs and farming implements. His second-in-command was Major Eden and they had two Yorkshire Captains, Farrer and Taylor, who knew the area. Bradshaw also relied on local people, who travelled the packhorse trails between Heptonstall and Halifax. Many of these were quick to come forward with intelligence.

On 21st October, Bradshaw set out to Sowerby, which he occupied for two days and from where he was able to spy on the Royalist garrison at Sowerby Bridge below. Royalist, Sir Francis Mackworth, a veteran of the battles of Wakefield and Adwalton Moor, who had taken Halifax and commanded a garrison there, now went on the offensive. He marched troops to Sowerby Bridge and led a charge uphill towards Sowerby.

Bradshaw and his men retreated without engaging the Royalists, but they would continue harassing Royalist sympathisers in the area. Two days later, Bradshaw marched his men to Warley, to the grand house of James Murgatroyd, a King’s man, which was quickly taken and which provided much needed arms and gunpowder. Forty-four prisoners were taken back to Heptonstall.

Bradshaw now set about strengthening his defences at Heptonstall as he must have known that retaliation would come. Barricades were put up and many huge boulders were placed strategically at the top of the hill called “The Buttress”, to heave down on any attackers. He set up patrols and posted look-outs on top of the tower of St Thomas a’Beckett Church.

Setting off at 3am on 1st November 1643, Sir Francis Mackworth, along with 400 musketeers and 400 cavalry, marched to Hebden Bridge, gathering at the riverbank by the bridge. Beyond the bridge was the “Buttress”, the steep medieval packhorse trail that led to Heptonstall. Bradshaw’s lookouts had seen the Royalists approaching and his men took up their positions.

…As the royalist soldiers and cavalry began the 500ft climb to Heptonstall at dawn, they were met with a cascade of falling rocks followed by the attacking Parliamentarians. Men were trampled underfoot by panic-stricken horses running back down the buttress.

hebdenbridge.co.uk

Royalist musketeers were hindered as their powder became wet in the raging storm…but the Parliamentarian defenders had taken steps to keep their own powder dry and their shots were much more effective. As the Parliamentarians rushed down the hill, hand-to-hand fighting took place…until eventually the Royalists gave ground. The Royalist force beat their retreat over the narrow bridge some plunging into the river to escape, only to be swept away by a raging torrent following heavy rain and some were drowned. They retreated towards Halifax, pursued for five miles by the exuberant defenders.

Captive Royalist soldiers and their injured were taken up to Heptonstall and locked in the church and the wounded were tended. Among the Parliamentarians who were wounded was Colonel Bradshaw himself. Bradshaw continued to lead his men from his sick bed for five weeks, when they continued to raid the Royalist gentry in the area and plundered and pillaged their homes.

However, Colonel Bradshaw’s health deteriorated until he eventually died from his wounds on December 8th. The Heptonstall registers contain the names of other men from both sides of the conflict who died from wounds inflicted in the battle. More than 100 civilian burials were also recorded that winter, far more than normal for the village. After Colonel Bradshaw’s death, Major Eden would take over command of the Heptonstall troops and turned out to be a very capable officer.

Approaching 400 years later, villagers still uncover musket balls in the area and a community play, performed in 2019, written by Michael Crowley and funded by Sky Arts, explored the conflict through the eyes of local spinners and weavers, whose lives and livelihood were disrupted by the war.

© Christine Widdall 2019